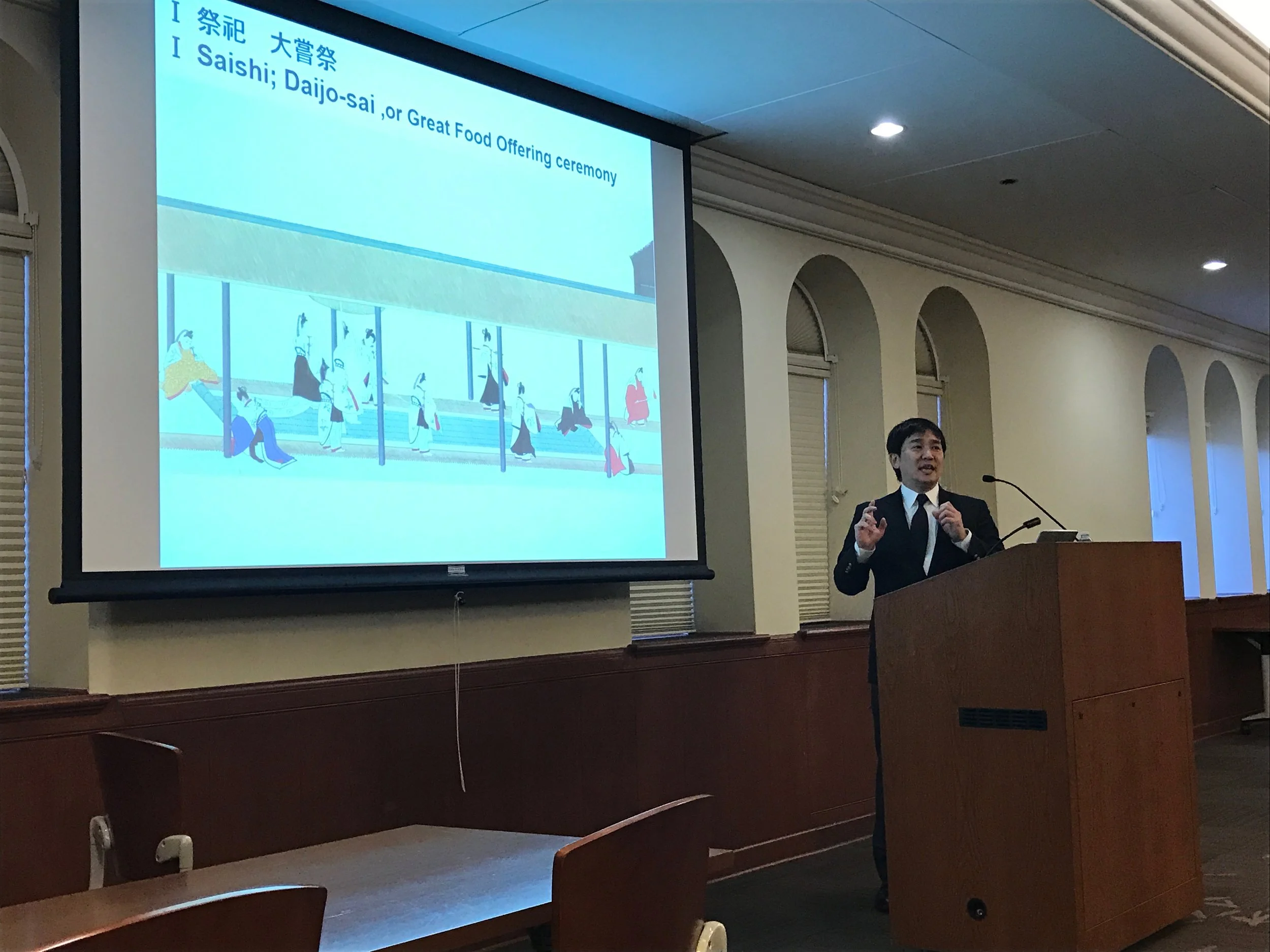

4:15-4:45 Prof. Inokuma Kaneki, Tokyo National Museum

“Research in the Material Culture of the Old Japanese Royal Court”

In the kind of class-structured society that existed in the pre-modern era, a person’s lifestyle corresponded to that person’s rank in the class hierarchy. Members of the court sought to pass down their ways of life to their descendants based on the formal manners and customs of the court, with the aim of preserving their special hierarchic status. The body of knowledge concerning these formal customs is known as 有職 (yūsoku). The essential aim of the court’s formal customs was to maintain order in the hierarchy. Courtiers were kept in line by their bureaucratic position, class, and ancestry. This order was physically embodied in the practice of ceremonial rituals that made use of the palace, furnishings, and costumes. In other words, the buildings, implements and clothing of the court were not only tools but also articles of material culture that, through their form and design, had the social function of signifying a courtier’s position and lineage, and the state of court ceremonial. As such the style of the court was formed through these articles of material culture. This use of material culture to differentiate between members of society and ceremonial events is a universal phenomenon that can be seen throughout world history.

It is particularly marked, however, in 礼制 (J: reisei, C: lǐzhì, or the system of protocol) that developed in ancient China. The form of government of the Chinese court, called 朝廷 (J: chōtei, C: cháotíng), which was based on the principles of protocol, was not only passed down to successive dynasties in China. Since it was a universal system of government that spread to the Japanese archipelago, the Korean peninsula, the Vietnam region, and the Ryūkyū Islands, the Chinese court style also influenced courts in other parts of Eastern Asia.

My discussion of the style of the monarch’s court in Japan is divided into the categories of rituals 祭祀 (saishi), the New Year’s Imperial Greeting ceremony 朝賀 (J:Chōga, C:Cháohè), and official events 公事 (kuji). 1) 祭祀 (saishi) The items of material culture used in the 大嘗祭 (Daijō-sai), or Great Food Offering ceremony were devices intended to project ancient customs. By preserving them, those ancient customs have been passed on down to the present day. 2) 朝賀 (Chōga) In embodying the principles of the chōtei court, the court style was formed by material culture such as palaces, furnishings and costumes that imitated items used in the Chinese icourt of the Tang Dynasty. 3) 公事 (kuji) The characteristics of era, region and ethnicity in courtesy-based East Asian imperial courts are most apparent in their inner courts (private space). In Japan’s inner court, annual events of the season emerged to form a court culture that was rich in elegance.

日本の宮廷を対象とする物質文化的研究

前近代の階層社会では階層ごとの生活様式が形成されており、公家階層が構成する宮廷では宮廷礼法に基づく生活様式が伝承された。この宮廷礼法の知識体系を有職という。宮廷礼法の要点は身分秩序の維持にあり、その秩序は宮廷人の官職・階級・家柄などによって正され、殿舎・調度・服飾などを用いた宮廷行事を実践するなかで形而下的に具現された。即ち、宮廷における建築・器物・衣服は生活用具であるばかりでなく、その形式や意匠によって宮廷人の身分地位や宮廷行事の状態などを表象する社会的機能を有する物質文化であり、それらによって宮廷様式が形成されていた。このように物質文化を用いて社会構成員の差別や儀式行事の状態を表象する行為は、古代中国で発達した礼制における顕著な現象であった。礼制の理念に基づいた朝廷という政治体制は中国の歴代王朝に継承されたばかりでなく、日本列島・朝鮮半島・越南地域・琉球諸島などにも普及した普遍的政体であるので、中国の宮廷様式は東アジア各地の宮廷にも影響を及ぼした。以上のような趣旨を踏まえて、本研究では日本の宮廷様式を祭祀系・朝賀系・公事系に分類する。

①祭祀系:大嘗祭に用いられた物質文化は古い習俗を投影する装置であり、これらによって太古の習俗が現代まで伝承された。

②朝賀系:朝廷の理念を具現するために、唐の宮廷で用いられていた物質文化の形式に基づいた宮廷様式が整備された。

③公事系:礼制に基づく東アジア宮廷では内廷に時代・地域・民族の特色が現出する。日本の内廷では年中行事が発達して雅趣に富んだ宮廷文化が形成された。